It’s one of many creative ways that area providers, patients and nonprofits have adapted to the challenges of treating breast cancer in the age of the coronavirus.

Support groups such as the Pink Ribbon Girls and the Noble Circle Project initially canceled some services but enhanced others, such as virtual peer support and meal delivery. Fundraisers have gone virtual.

Providers compensated for the absence of family members at appointments by increasing the number of telehealth visits. “Knowledge is power,” said oncologist Nkeiruka Okoye, who is an MD Anderson Cancer Center certified physician through Premier Health. “Videoconferencing puts patients and their families in the driver’s seat; they are there together.”

‘Cancer is secondary; my family is first’

The reaction from fellow patients and staff to her boxer costume boosted Penrose’s morale and self-confidence. “I would rather have them cheering me on than crying for me,” she said.

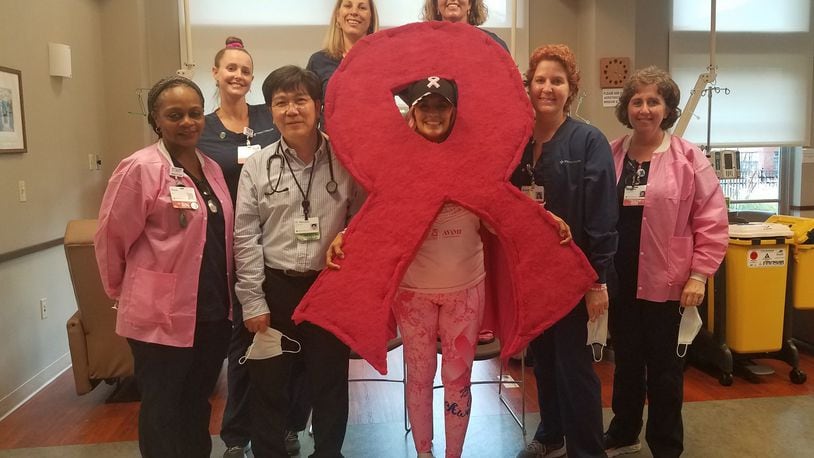

Penrose has continued to don a superhero costume at subsequent appointments, appearing as Batgirl, Wonder Woman and even a huge pink ribbon to symbolize breast cancer awareness.

Before Penrose’s appointments, the staff now finds itself wondering, “Who is Julie going to be today?”

“I can’t say enough about Julie for going through all of this and remaining so positive,” said oncology nurse Tracy Adrian.

For Penrose, her family’s reaction is the biggest reward for her perseverance — and her greatest inspiration for each week’s costume. “I didn’t want them to be scared and to be worried about me,” she said. “Cancer is secondary; my family is first.”

As a breast health navigator, Adrian becomes the patients' point person from diagnosis to recovery. She attends their appointments, guides them through their treatment plan and connects them with local support groups and financial resources such as the Breast Cancer Endowment Fund of Clark County and the Breast Cancer Fund of Ohio. “Can you imagine fighting cancer during this pandemic?” Adrian asked. “People have lost jobs and sources of income, and that’s such a huge stressor at a time when they are starting treatments. Fortunately, we have all these community organizations that are fantastic and that are helping so much.”

As a safety precaution, family members and friends are not allowed to join patients in the infusion suite. “It’s scary going back there by yourself not having that support person with you,” Adrian said.

Adrian and her colleagues frequently check in with patients in the infusion room. “We have stepped up, and we have developed even closer relationships with our patients,” Adrian said.

Penrose said it has been difficult not being able to have her family’s moral support during chemo. “But the staff at Mercy Health are such supporters, and they make you feel you are not alone,” she said.

That commitment carries over into the staff’s private lives, Adrian said: “Our patients are immuno-suppressed, so we don’t go to restaurants. We don’t want to put our patients at risk. We feel like we are a team with our patients; we are helping each other out.”

Cancer patients face high risk from COVID

Patty Young of Monroe had received a clean mammogram result only last December, but in March she noticed a hard lump the size of a duck egg in her right breast.

The diagnosis was a shocking one: a fast-growing cancer that had spread to the skin of her breast. Even worse, her cancer had coincided with the beginning of lockdown. She couldn’t bring her husband, mother or son with her to any of her 20 chemotherapy treatments at the Atrium Medical Center in Middletown.

“Through all this, the cancer keeps going,” said Okoye, who is Young’s oncologist. “It is taking a mental toll on everybody. It is already stressful enough to be diagnosed with cancer, and these patients have the extra concern of getting active cancer treatment during the pandemic.”

Cancer patients typically are cautioned to avoid crowds, but that is even more imperative during the pandemic. Their risk of death is 16 times the national average, Okoye said: “They are not going to be the ones arguing about wearing masks or not. They are going to do what they have to do because they want to stay alive.”

That means Young hasn’t been able to return to her job as a cashier at the Monroe Kroger store. “I miss my customers,” she said. “I have always loved my job. I don’t let anybody get past me without saying hello to them. The love they have shown me is unbelievable.”

The Monroe school district even sponsored a “Miss Patty” day, with schoolchildren showering her with shopping bags full of cards. One little boy drew a picture of the Avengers attacking her cancer.

“I was just overwhelmed,” she said. “They make me feel like a princess.”

Young has responded well to treatment, Okoye said, while maintaining a remarkably upbeat attitude. “This is a hard thing, and there’s no way to sugarcoat it,” she said. “The treatment is intense and aggressive, and you get to feeling low. Being able to have a positive way of looking at things helps that whole process.”

Fundraising shortfalls — and increased need

Fundraising has proven a challenge for many cancer-related charities that rely heavily on galas, fashion shows and other large social events to generate revenue.

“We are learning how to pivot and learn how to get new sources of funding because we are determined not to quit providing direct services to our clients,” said Vicki Varvel, vice president of operations for the Pink Ribbon Girls, a Tipp City-based nonprofit that provides free meals, housekeeping, transportation and peer support for breast and gynecological cancer patients.

The agency has increased its grant-writing and has turned to virtual fund drives, such as exercise challenges.

During the height of the pandemic this spring, the Pink Ribbon Girls initially suspended housekeeping for fear of contamination, and the agency has canceled this year’s “Four By the Shore,” an all-expenses paid Thanksgiving week Florida retreat for Stage 4 cancer patients and their families.

But the agency has ramped up other programs. The demand for peer support sessions — now conducted virtually — has increased nearly tenfold since the start of COVID, and at the height of the pandemic, Pink Ribbon Girls was supplying five meals a week, instead of the usual three, for their clients and their families. In August the Pink Ribbon Girls reached the milestone of supplying 500,000 meals (since its inception in 2012) to clients in Dayton, Cincinnati, and Columbus as well as St. Louis, Missouri, and the Bay area in California. “Our clients are immuno-compromised and shouldn’t be going to the grocery store,” Varvel explained.

Canceled programs, renewed commitment

For the first time in 15 years, the Noble Circle Project — a support group that serves Miami Valley women from five counties — was forced to cancel its spring “New Sisters” program, a 10-week intensive session focusing on nutritional education, complementary energy techniques and peer support. A weekend retreat kicks off an intense bonding experience that leads to lifelong friendships and transformed lives.

“It was really, really sad, the thought that we couldn’t bring in this group of women who needed that help, that connection,” said past Noble Circle chair Rhonda Traylor of Huber Heights. “But we just couldn’t put our sisters at risk.”

Debbie Newton of St. Mary’s felt profoundly disappointed that she couldn’t start the program in the spring. At 68, she had recently finished radiation therapy and decided to retire after a distinguished career as a certified nurse midwife.

“I just knew I was called to do this program,” Newton said. “It was a spiritual thing, and I needed it.”

Newton was diagnosed with Stage 1a breast cancer in December, and had surgery — partial mastectomy with lymph node removal — in January. At times the pandemic created a sense of isolation. “You had to wait in the car for radiation, and you weren’t allowed to bring anyone in with you for treatment,” she said.

Fortunately, the Noble Circle’s New Sister program resumed in September with a social-distancing fall retreat, followed by weekly three-hour sessions that are so beneficial Newton doesn’t hesitate to make the 90-minute drive from St. Mary’s. “You are surrounded by your sister cancer survivors who walk you through the process, and your innermost fears and vulnerabilities are exposed,” she said.

That camaraderie simply can’t be replicated over Zoom, Traylor said. The fall program was limited to five participants — about a third of the usual number — for the sake of safety. But Traylor, who helped out during the retreat weekend for Noble Circle Group 33 in September, witnessed the same relationship-building as when she took part in the retreat weekend in 2009, as part of Group 11. “We are sisters,” she said. “That’s one of the primary parts of the program — being able to talk to one another, share stories with one another, lean on each other and offer support.”

Hundreds of Noble Circle sisters from the previous 32 groups remain active in the program, finding new ways to gather — taking hikes in local parks — and volunteering to help the women in Group 33. “I don’t know what I’d do without Noble Circle,” Traylor said. “My sisters are forever.”

About the Author