She told the Dayton Daily News in 1967 she could not remember a time when education did not impact her life.

“My father was the oldest of nine and sent all eight brothers and sisters through college,” she said. “We were never kept out of school for anything. Education, education was all we heard, so I never felt there was anything else in life but to go to school.”

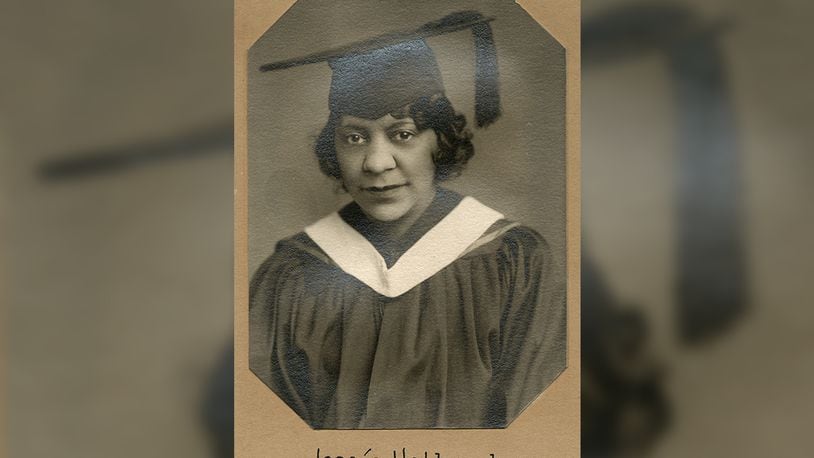

Hathcock, a literature teacher and Dean of Girls at Dunbar High School for 35 years, was known for her encouragement and devotion to students whom she called her “proteges.”

She used her own money to pay for lunches, clothes, commencement robe rentals and shoes.

“I never asked directly if they needed money,” she said. “I asked them to do little errands that really didn’t need to be done and would give them some change for it.”

Hathcock paid for students’ college applications and wrote letters to universities on behalf of them. During a college visit for one student, she talked to the professors and asked them “to throw things his way” to make tuition affordable.

She invited cultural dignitaries to her home to speak to students. The poet Langston Hughes, NAACP president James Weldon Johnson and W.E.B. DuBois, the editor, scholar, educator and civil rights activist, were among the visitors.

A prolific world traveler, Hathcock used donations received from “travelogue talks” to finance the Jessie Hathcock scholarship, which was set up before she retired in 1964.

In return, students referred to her as “blessed lady” and “majestic lady,” and a pre-law student dedicated a poem to her, writing, “You instill the hope I need for every tomorrow.”

Hathcock’s grandson, Lloyd S. Hathcock Jr., 74, also a retired Dayton schools educator, said his “Mama Jessie” was dedicated to students because she loved people.

Her mission, he said, was to be “a ray of light that will shine out to the community so they could find their way.”

Jessie Hathcock’s light shone brightly in Dayton.

Among her many accomplishments was organizing the Dunbar PTA, founding the Dayton and Miami Valley Committee for UNICEF and working with the Red Cross, the Dayton Council of World Affairs, Children’s Medial Center and the City Beautiful Council.

She was also one of the Top Ten Women of Dayton in 1966 for promoting higher education to students.

In 1978, Hathcock achieved another first at the University of Dayton when the institution awarded her an honorary doctorate in humanities, making her the first African American woman to be honored in that manner.

Hathcock Jr., who took photos of his grandmother receiving her honorary doctorate that day, said she was humble and rarely mentioned her accomplishments, but was pleased to be acknowledged for her contributions.

“It was such an honor for her to receive a degree and be recognized for all the things that she had done for people and the city of Dayton,” he said.

That honor came more than five decades after she first applied to the university but was rejected based on race. She was later admitted but only allowed to take classes at night.

Last fall, months after committing to action steps toward becoming an anti-racist university, Eric F. Spina, the university president, informed the university community of a letter written in 1930 that demonstrated “clear evidence of systematic racism at UD.”

The letter was written in response to an inquiry from W.E.B. DuBois, editor of The Crisis, who asked about the number of African American students at UD.

The reply, written by Brother Joseph Muench, S.M., and dated June 13, 1930, notes there was “one student of Negro descent” at the university – “Mrs. Jessie V. Hathcock.”

The letter states she had recently graduated, was a “very satisfactory” student and took evening courses at the school.

“We do not admit Negroes into our day classes because of the considerable number of students we have from Southern States. However, they are admitted in the Law Classes and the Evening College Classes which are almost wholly composed of Dayton people,” Muench wrote.

President Spina wrote, “This demonstrates that the University allowed Jim Crow segregation to extend to our campus and is concrete evidence of the kinds of systemic racism that denied opportunity to generations of people because of the color of their skin.

“The University was wrong to engage in this practice. We express our deep remorse and apologize as president and rector on behalf of the University.”

Hathcock died in 1986. In 2004, the Jessie V. Scott Hathcock Memorial Scholarship was established at UD to assist traditional or non-traditional students, with preference given to female, African American students majoring in education or English.

Last month, the university announced that its newly renovated computer science building would be named to honor Hathcock.

“I’m glad I was sitting down when I heard. I was about ready to either pass out or cry,” Hathcock Jr. said of the honor bestowed upon his grandmother.

“She would have loved it,” he said. “She would have taken it in stride but in her own way been elated.”

About the Author